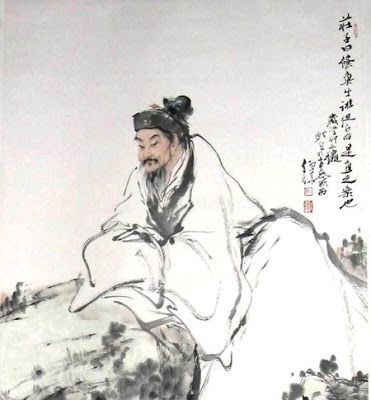

Chuang Tzu: The Cook and Mastery clipping

January 15th, 2019

I

have found an interesting discussion on the Cook by Chuang Tzu on Wikipedia http://www.philosophy.hku.hk/ch/zhuang.htm

It

does begin to get at what mastery begins.

Cook Ting was slicing up an oxen for Lord Wenhui. At

every push of his hand, every angle of his shoulder, every step with his feet,

every bend of his kneezip! zoop! he slithered the knife along with a zing, and

all was in perfect rhythm, as though he were dancing to Mulberry Grove or

keeping time as in Qingshou music.

"Ah, this is

marvelous!" said Lord Wenhui. "Imagine skill reaching such heights!"

Cook Ting laid down his knife and replied, "What I care about

is a tao which advances my skill. When first I began cutting up oxen, I

could see nothing that was not ox. After three years, I never saw a whole ox.

And nownow I go at it by spirit and do not look with my eyes. Controlling

knowledge has stopped and my spirit wills the performance. I depend on the natural

makeup, cut through the creases, guide through fissures. I depend on things as

they are. So I never touch the smallest ligament or tendon, much less bone."

"A good cook changes

his knife once a yearbecause he cuts. A mediocre cook changes his knife once a

monthbecause he hacks. I have had this knife of mine for nineteen years and

I've cut up thousands of oxen with it. Yet the blade is as good as if it had

just come from the grindstone. . . . "

"Despite that, I

regularly come to the end of what I am used to. I see its being hard to carry

on. I become alert; my gaze comes to rest. I slow down my performance and move

the blade with delicacy. Then zhrup! it cuts through and falls to the ground. I

stand with the knife erect, look all around, deem it wonderfully fulfilling,

strop the knife and put it away."

Traditional

interpreters stress the mystical flavor, the reference to tao. One way to read the claim that tao advances skill is as the claim that it surpasses

skill. This traditional commitment to a mystical, monistic tao requiresthat accomplishment not be related in ordinary ways to practice and skill. It

must come from some sudden and inexplicable insight, mystical experience or

attitude. This interpretation coincides with a familiar Zen view. The absolutist

monistic interpretation should resist the suggestion that Ting knows his tao

and still can improve. How can you have some of a tao that has noparts? When you have it you suspend entirely all thought and sensation.

Cook

Ting's story clashes slightly with this religious or mystical view of Chuang

Tzu's advice. His description implies that Ting has a hold on a particular way

of doing one thing. Ting's way is developing. He continues to progress inpursuing his skill by tracing his tao to points beyond his previoustraining. When he comes to a hard part, he has to pay attention, makedistinctions, try them out and then move on. This supports the view thatdeveloping skill eventually goes beyond what we can explain with concepts,distinctions, or language. The focus required for a superb performance may not

be compatible with a deliberating self-consciousness.

The

Butcher does not say that he began at that level of skill. He does not report

any sudden conversion where some mystical insight flowed into him. He does not

say that he could just get in tune with the absolute Tao and become a

master butcher automatically. And he does not hint that by being a master

butcher, he is in command of all the skills of life. He could not use his level

of awareness at will to become a master jet pilot or a seamstress. His is not

an account of some absolute, single, prior tao but of the effect of

mastering some particular tao. We all recognize the sense of responsive

awareness which seems to suspend self-other consciousness.

It is natural to express this ideal of skill mastery in the language whichsuggests mystical awareness. It does normally involve suspension ofselfconsciousness, ratiocination and seems like surrender to an external force.

That language should not confuse us, however. Chuang Tzu's mingillumination

should help us see that the full experience is compatible with having his

perspective on perspectives.

Cook Ting can be aware that others may have different ways to dissect an ox. Hesimply cannot exercise his skill while he is trying to choose among them. Welose nothing in appreciating the multiple possibilities of ways to do things.In realizing a tao of some activity in us, we make it real in us. It isneither a mere, inert, cognition of some external force nor a surrender to astructure already innate in us.

Note,

further, that Cook Ting's activity is cutting--dividing something into parts.

When he is mastering his guiding tao, he perceives a world in which theox is already cut up. He comes to see the holes and fissures and spaces asinherent in nature. That seems a perfect metaphor for our coming to see theworld as divided into the natural kinds that correspond to our mastery ofterms. When we master a tao we must be able to execute it in a real

situation. It requires finding the distinctions (concepts) used in instruction

as mapping on nature. We don't have time, anymore, to read the map, webegin to see ourselves as reading the world. Mastering any tao thus

yields this sense of harmony with the world. It is as if the world, notthe instructions, guides us.

Thisfeature of tao mastery explains the temptation to read Taoist use ashaving become metaphysical. Guidance may, in the first instance, be broadly

linguistic--telling, pointing, modeling. The choice of a butcher for thisparable seems significant too. Butchering is seldom held as a noble profession.

Even the "Ting" may be significant--it may not be the cook's name but

a sign of relatively low rank--something like an also-ran. Other popular examples

of the theme include the cicada catcher and wheelwright. Chuang Tzu probably

intends to signal that this level of expertise is available within any

activity. Common interpretations, however, suggest that some activities are

ruled out.

Theexamples above, together with Chuang Tzu's obvious delight in parable, fantasy,and poetry invite the common hypothesis that, in the West, he would be aromantic--suspicious of direct, reasoned, logical discourse in favor of themore "emotional" arts. At least, one should eschew "intellectual"activities. That he is critical of Hui Shih, the alleged logician, supportsthis reading. The problem is that Chuang Tzu's parallels his comments about Hui

Shih with similar comments about a lute player. Furthermore, the criticism does

not seem to be the activity, but the search for absolute know-how. Chuang Tzu's"criticism" is that in being good at X, these paradigms of skill aremiserably inept at Y. This is another example of ch'eng (completion)

which Chuang Tzu argues is always accompanied by hui (defect).

Wemay achieve this absorption in performance by achieving skill at anytao--dancing, skating, playing music, butchering, chopping logic, lovemaking,skiing, using language, programming computers, throwing pottery, or cooking. Atthe highest levels of skill, we reach a point where we seem to transcend ourown selfconsciousness. What once felt like a skill developing inside us, beginsto feel like control from the natural structure of things. Our normal abilityto respond to complex feedback bypasses conscious processing. In our skilledactions, we have internalized a heightened sensitivity to the context.

These

reflections lead us to a problem with "achieve tao mastery" as

a prescription. I shall argue that the problems are both textual and

theoretical. On other places, (as we noted above) Chuang Tzu is more equivocal

about the value of mastery. Any mastery, Chuang Tzu notes, must leave something

out. Most particularly, to master any skill is to ignore others. Chuang Tzuremarks that masters are frequently not good teachers. They fail to transmittheir mastery to their sons or disciples.

ChuangTzu directs our attention to this problem with the glorification of total skilldedication and mastery. We trade any accomplishment at one skill for ineptitude at some other thing. The absent minded professor is our own favorite parody. If

the renowned practitioners have reached completion, he says, then so has

everyone. If they have not, then no one can. From the hinge of ways

perspective, we no more value the world's top chess player than the world's

finest jack of all trades. We need not read Chuang Tzu as advocating

specialization per se.

Thus

the three parts in Chuang Tzu's dao pull in separate directions and we

must treat each as tentative and conditional. The flexibility advice seems hard

to follow if we also accept convention and work for single-minded mastery.

That, in the end, may the message of perspectivalism. We have limits, but we

might as well get on with it.

Measure

Measure

Keep in touch!