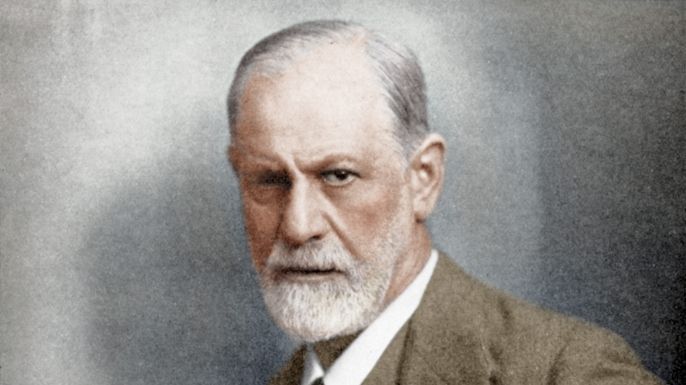

Freud On Transience

March 26th, 2018

Freud ruminates on the transitory nature of life and the beautiful things in life. This essay prompts a conversation about a variety of topics Freud raises, from death to libido to war.

Notes

The two people have objections to the transience of all things. Rebellion after the fact. Wishful thinking. Transience makes things more valuable.

Unrelated to this story: Aristotle has his chains taken off his legs and his legs feel better. But his legs would not feel good if there had been no change. So you cannot have pleasure without pain.

The absence of transience is something eternal, but if you have something eternal then it’s constant. There is no variance in it. Even to subjectively distinguish between A and B you need some type of difference. You need a change.

We are beings that seem to want to and need motion. You want transience because stasis is death.

The pain of thinking that something is transient necessarily comes along with the pleasure of its beauty. Maybe there is a necessary connection between the two things. Somehow this experience of beauty without experience of transience would be less. To what extent are we — as beings in motion — attached to their persistent character. It looks like those two aspects make some kind of valuable contribution to our sense of the things around us. Particularly their beauty.

Can you appreciate all the joys of peace without experiencing or seeing the horrors of war?

Sidebar Commentary: You cannot understand what is beautiful without having understood what is ugly. If you have not seen the opposite, then all have you seen is a spectrum of beauty.

When you are young, and adolescent, you fall in love with many of the things around you. Freud says that libido is directed inward until it is directed upon objects during adolescence. And he suggest that as you get older your libido drops.

There is some, subjective, quasi-truth and that your libido stay somewhat constant while everything around you changes.

There is no rational account for why we feel bad about the transience in beautiful things.

What is it in our attachment to things and our mourning when we lose them? We don’t really know. We know it happens but not why it happens?

Could pleasure be lessened by the fact that you know it is going to end? That does not mean you want to be a static being.

Sidebar Commentary: This is why framing is important. Jordan Peterson talks about this. There is tragedy and tragedy is the loss of something that you love or a situation in which is unfair or unjust in which you lose something beautiful or something is not as permanent as you would like it to be. Instead, we must except this and Freud suggests that we move on. I agree except that Freud does not bring it to its natural conclusion. The natural conclusion is that you need to accept tragedy and attempt to bring as much good as possible — through your actions and words — to the world… as long as you have skin in the game and as long as you do not transfer risk to others such that you don’t bear the risk yourself. You need to grow and thrive.

Being taciturn is kind of a strategy for avoiding mourning. You don’t mourn but you also can potentially not love (loss of objects of your libido).

Postulating: In war — or combat (e.g., BJJ, wrestling) you are purely in the moment. At least when engage in battle. Even when there is death and distraction there is not an experience of time.

System boundaries: Views of war are outside of war not inside of war. While I have not experienced war, the amount of change in your emotional being is static in war and stored somewhere else and when you are outside of war it is released almost all at once. Understand life and death, ugly and beauty in a different way.

— —

Notes Sources:

Combat and Classics, Ep. 17: Freud on Transience

Apple Podcasts