Slaying the Dragon Within Us

March 7th, 2018

Notes

Pay attention, or else

Mythologies as Compression Algorithms

The materialistic view cannot tell us anything about consciousness.

Plato proposed that all knowledge was remembering. We do not believe that today because we believe that we gather knowledge as consequence of contact in with world. But there are some things that are predicated on this idea remembering since it strikes such a deep cord.

Models of the world that include phenomena like consciousness, emotion, motivations, actions, and interactions are generally portrayed formally in stories and not in scientific theories. It turns out that stories have an identifiable structure, even a grammar that makes them comprehensible. Furthermore, it turns out that the simplest stories, especially when they are elegantly structured, have an unbelievably profound underlying meaning. And you can frequently see this most particularly in children stories.

Why do mythological stories strike a deep cord?

The story is no more about the props in the world than a play is about the props on the stage. The drama is about the manner in which people actually exist, the emotions that they feel, the motivational states they encounter, the problem they have to solve, and the way they interact with each other. And plays are the thing from that particular perspective in which we can capture those aspects of our experience that are not only real but essentially human.

Whenever you do anything, you interact in a bounded world.

Maybe there is a pattern for encountering unexpected things. Maybe there is a proper way. In our collective wisdom as human beings we have gathered up representations of ways to encounter the unexpected that we put forth in stories. How should you face what you do not understand?

Why would something terrible and ancient hold a treasure?

The Fundamental Nature of Experience

There is a map of human motivation that is easy to understand if you go to a movie (rather than a book, because you would need to translate a book to experience it). What you’ll see, regardless of the country it’s made — or the language — there’s certain things that always happen. Like, two broad classes of fiction: Adventure and romance.

What is an adventure? To go to new lands and discover something new, and become transformed as a consequence.

What is a romance? To meet another person who is certainly as complicated as anything you could meet meet on an adventure, and again to be transformed as a consequence of that contact.

These are two fundamental plots. Why are there fundamental plots of movies? Why do we understand them so much without them being explained to us?

It’s because, fundamentally, we are all very, very similar. We have a finite set of basic needs. For example in an action or romance story, you encounter something and are transformed by it.

Thirsty people would rather have water and hungry people would rather eat. These motivations color what will be conceived of as our ultimate destiny. In the old testament paradise was milk and honey.

The underlying motivational system of ours set us up bounded worlds in which we live in. If you fall in love with someone and you construe your destiny as with being with them, any indication of them being pleased with you will create a positive rush of emotion. Why? Because our emotional systems are set up so that any signs that we are moving towards our goal is responded to with a rush of positive emotion. And conversely, a frown from the person who you love is met with a flood of negative affect. Why? Because anything that stops us on the path that we have chosen creates a negative emotion.

We feel the protagonist we embody.

So when you say that you understand someone else, what you mean is your body is set to do exactly the same thing their body is. And your emotional systems are locked on exactly the same way they are so when they experience something you experience an echo of it. That is what understanding means.

Those neural systems that allow us to embody someone else and to imitate them are right underneath the structure we have evolved to use for language. What that indicates is that mostly what we use language for is to tell stories about the way people act so we can derive information from it. Not about what the world is made out because we do not really care about that in some fundamental way. Instead, how should we act? That is the fundamental question.

Ancient Stories

Ancient stories have rituals, have mythologies. We have ancient written stories.

Oral traditions are over 20,000 years old and ancient Sumerian texts — like the Enume Lish — are as old as four thousand years old. What do they mean? What are they good for?

A myth is the most interesting story that you could tell. It is the compression of hundreds of the best stories which are compressions of tens of thousands of stories and experiences which contain information on how to act.

Sidebar Commentary: Myths are compression algorithms that are instructions on how to live your life. Collectively, they are circumambulations of the human experience, and how to act in the world.

Virtually every story that you see has an underlying structure which is compelling to you. That is why your attention is captivated by them.

We always parse up the world in terms of what it is good for; how it could serve your purposes. The question is not parsing parts of the world and what is good for you, such as chairs. The complicated question is what do you do when something that you do not expect happens.

If you encounter something unexpected the first thing you see is not the world, the first thing you see is just a sense of discomfort and fear, combined with some latent curiosity that the world is not the way you thought it was. Now, how do you find out about how the world is actually like? You have to investigate it. You have to take a risk and move forward. Find the thing that you are bordering on avoiding and go in and map it. The simple world of objects is what we just see. The real world is much more complicated. When you just look at something you see a very simple representation of what is actually there. For example your computer not working could be a result of a solar flare.

What is embedded in everything that you are afraid of? Absolutely everything you need to find!

Run from what you are afraid of and run from everything that you need to find. The thing that you most need will always be found where you least want to look.

What happens when you go after the dragon? You get a piece of it (hopefully).

You have absolutely everything you need. But you need to use all of it. If you run away from any of it, in particular the parts that frighten you, you do not get that piece of the Dragon. If you miss even one piece then there is a chink in your armor, the place where you are vulnerable. If you make just one mistake, you lessen yourself. If you lessen yourself then you are going to run away more. Not only that but if someone wants to lean on you they will not be able to lean on you because you will just fall over. What if we were adapted to the world, I mean really adapted to the world, so that if we had made use of all the talents we had, then it will be OK. What is it was the case that if we set out consciously to never run away from something that we shouldn’t run away from, that everything would be alright? Well, you can think whatever you want to think, but this is what I think: I think it is amazing that a little kid’s book has all that information in it. So you might ask yourself when you leave, if that information isn’t true, then how the hell did it get in that book? That’s it.

— —

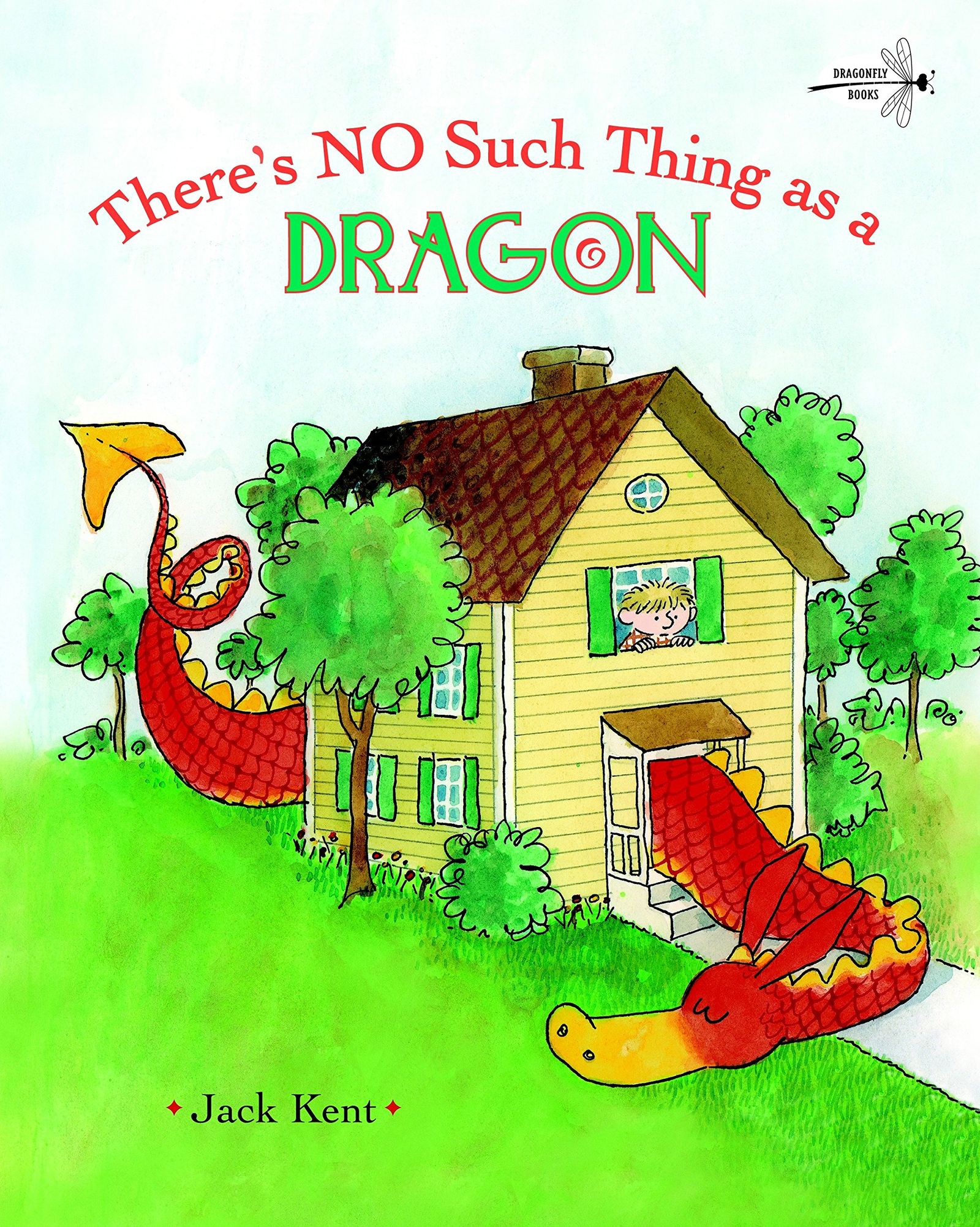

There’s No Such Thing as a Dragon by Jack Kent

JBP, Ep. 6: Slaying The Dragon Within Us

Apple Podcasts